Dunia Perpustakaan | Public libraries have long served as infomediaries between government and the public. This intermediary role, a mainstay of our democratic society, is now more vital than ever: Our profession’s commitments to providing equitable access to government information (Robinson & Mather, 2017; Yoon, Copeland, & McNally, 2018; Bertot et al., 2006; Whitacre & Rhinesmith, 2015) has new urgency, as we support the public in confronting a pandemic, recession, civil unrest, and the associated onslaught of conflicting, misleading, and false information. With the acceleration of open data, libraries can expand the scope of their infomediary capacity to include providing access to valuable structured government information. In fact, as suggested in a previous Library Journal article, libraries have a professional obligation to do so, especially at the regional level (Enis, 2020), and they are beginning to take on a range of roles, as data stewards, publishers, educators, and partners in data stewardship (IFLA, 2020).

Recognizing the opportunities and the challenges of this new area of responsibility for public libraries, the Open Data Literacy (ODL) project has been fostering the advancement of open data for the public good through education informed by engagement and research. Based in the Information School at the University of Washington, ODL was launched in 2016 with funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Here we provide an overview of ODL work to date. We also share highlights from a survey of the current landscape of open data in public libraries in the state of Washington that shows that libraries large and small, urban and rural, recognize the importance of open data for their communities, and that many are already integrating open data into the purview of their service commitments.

PUBLIC SECTOR PERSPECTIVE

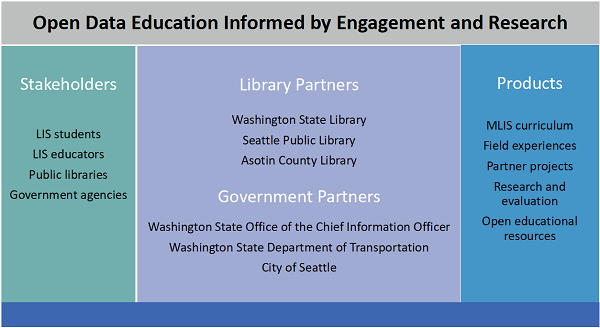

Open data endeavors necessarily cut across the public sector. Expectations for public access to data are growing within all levels of government and among the people we serve in our libraries, with the promise of fostering civic engagement, increasing transparency of government operations and accountability of elected officials, informing decision-making by citizens, and fueling economic progress (Allen, Stewart, & Wright, 2017; Davies & Bawa, 2012). Achieving this potential requires that data at the federal, state, and municipal levels are made accessible and usable. At the same time, the public must be able to understand and apply the data made available to them. Thus, for people in communities to benefit from open data, investments must be made in transforming data for access and use, developing infrastructure and products such as dashboards and visualizations, and supporting data literacy among the public. As a whole, these responsibilities will need to be shared by local government and libraries working together, equipped with new professional competencies. With workforce development as a primary aim of ODL, stakeholders include public libraries and government agencies, as well as library and information science (LIS) students and educators.

To closely align our work with public sector perspectives and needs, ODL engaged multiple partners from state and local government as well as public libraries. These relationships were fundamental to building capacity and assuring practical applicability of our interdependent work plan of education, engagement, and research activities. Library partners represented urban, rural, and state libraries; government partners included both state agencies and city government. The government partners were essential to understanding aspects of the open data movement from the inside, where data resources are generated. They offered a direct connection with current practices and challenges from the perspective of data producers striving to meet new demands for government transparency. Library partnerships allowed us to contribute to and learn from plans, programs, and services emerging within individual libraries, assets that were greatly extended through our partnership with the Washington State Library (WSL).

ODL partners informed curriculum development, contributed to in-class instruction, sponsored and mentored internships and capstone projects, and collaborated on research. At the same time, student learning was greatly enriched, public sector interests were well represented, and the partner organizations made headway on their open data priorities. Our partnership with WSL was the most multifaceted. WSL hosted multiple interns, fostered dissemination to state and national library organizations, and ultimately established a new professional position dedicated to open data. WSL also collaborated on a statewide survey on Public Libraries and Open Data, discussed further below. ODL stakeholder groups, partners, and activities are outlined in Figure 1. In the discussion that follows we highlight how the partnerships informed curriculum advances and enriched the student experience through experiential learning.

|

Figure 1 Framework for Open Data Literacy education activities. |

OPEN DATA CURRICULUM

ODL curriculum efforts built on a base of existing data curation course content designed to prepare professionals for work with data resources and services in academic libraries and repositories. Coursework was revised and extended to also cover open data for the public, with a focus on work in public libraries and the public sector more broadly. The curriculum reflects the evolving roles of library professionals as infomediaries of government information—from acquiring, organizing and preserving library materials, to proactively designing, implementing, and maintaining consistent access to data and technologies in the public interest; curating and analyzing open data; and developing programs and resources to support public data literacy. In particular, we worked to fill a gap in practical technical expertise for students entering the public library workforce through lab-based courses that emphasize the use of open data and development and maintenance of prototyped data systems. Courses were developed, tested, and iterated to support students with limited technical background in cultivating and practicing new competencies with oversight by LIS instructors.

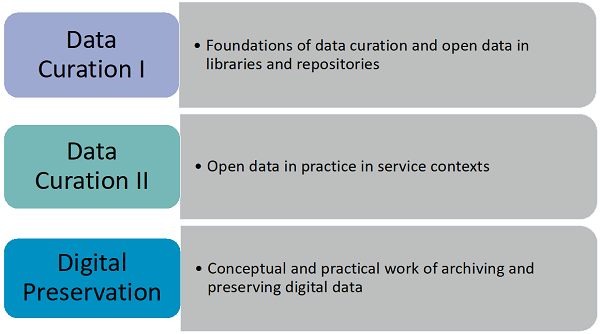

The core open data curriculum consists of a three-course sequence in the Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) program: Data Curation I, Data Curation II, and Digital Preservation (Figure 2). Collectively, these courses introduce emergent competencies for public and technical service roles in contemporary librarianship and strengthen skills through hands-on work with public open data. Students are exposed to best practices working with and packaging data for reuse by diverse user communities, selecting and applying appropriate data standards, developing data governance policy, and evaluating data to align with ethical expectations of both data producers and data subjects. Classroom sessions are enriched by hosting practicing librarians, data managers from city and state agencies, curators from not-for-profit groups, and industry technologists who provide real-world data use cases that contextualize and ground topics introduced through lectures and lab work.

The first data curation course covers the foundations of data curation and open data in libraries and repositories. Students develop a protocol for curating open data; create new metadata and documentation to make this data accessible; and then publish data to a public repository following W3C’s conventions for open data on the web. The second data curation course concentrates on open data in practice in service contexts. Building on skills gained in Data Curation 1, students engage in a series of lab exercises to understand integrating different open data sources, obtain data using a public API, create data models that describe the contents of integrated data, and then engage in a multi-week activity of configuring existing data repository software (CKAN and Dataverse) to publish new collections of integrated open data to the web. Digital Preservation consists of conceptual and practical work archiving and preserving digital data. Conceived of as the final course in the ODL sequence, it includes lab exercises that focus on carrying out maintenance tasks for existing digital data collections, and then translating skills in curating data to verify and validate collections of data that are found on the web.

|

Figure 2 Course sequence with practical objectives. |

EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING

Field experiences for students were a particularly significant outcome of the ODL project, made possible through our strong partnerships. While hundreds of students have benefited from the core curriculum, dozens supplemented their classroom education through internships and capstone projects. The ODL summer internship program was the cornerstone of our experiential learning work (Weber, Norlander, & Palmer, 2018). Students were matched with public sector partners for 10-week positions designed to translate classroom skills into hands-on projects. Working closely with a mentor within the library or government agency, interns researched, proposed, and then executed an open data initiative. They developed open-source software, curated new open data collections, created open data policies, and recommendations, designed open data programs for the public and practicing library personnel, and made other substantive contributions to open data priorities for the host organizations. These field experiences contributed to strong job placement for the interns, and, as mentioned above, one evolved into an Open Data Literacy Consultant position in the Washington State Library that is now supporting new open data efforts across the state.

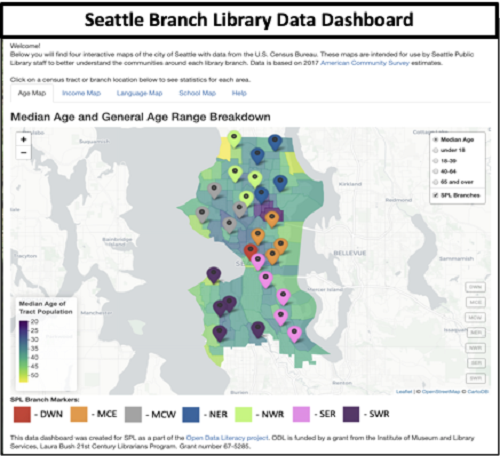

A number of other internships had impacts well beyond their initial scope. An intern based at Seattle Public Library produced a prototype of a tool to facilitate customized outreach by branch libraries. The dashboard, which provides meaningful visualization of demographic data associated with neighborhoods (Figure 3), encouraged branch staff to embrace a data-driven approach to understanding characteristics and particular needs of local communities (Ostler, Norlander, & Weber, 2020). The capabilities demonstrated by the intern’s work spurred a larger initiative to explore how open data can support effective program, service, and partnership planning in public libraries across the United States (imls.gov/grants/awarded/lg-246255-ols-20). Also furthered through subsequent support from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), another internship placement at a rural county library offered a model of how small libraries can work in coordination with local government to publish local open data (imls.gov/grants/awarded/lg-28-19-0229-19-0).

|

Figure 3 Prototype neighborhood data visualization tool. |

EDUCATIONAL LESSONS LEARNED

Formative evaluation of curriculum and field experiences provided the opportunity for iterative development of classes and the internship program each year. For example, early interviews and focus groups with students and partners highlighted the need for more practical technical content and further attention to the community engagement dimension of open data competencies. In response, we implemented modules on development of high-quality prototypes and advocacy approaches for work on data release from government agencies. Feedback from students also confirmed successful application of classroom learning in internship projects. For example, curriculum on metadata across two data curation courses equipped a student to work on systems re-architecture of the Seattle Open Data program that resulted in a sophisticated set of recommendations for standards adoption. Another student directly applied coursework on programmable interfaces in an internship project on automating data requests, noting: “I just never realized how useful APIs are. It took the internship to really show me.” In another case, the value of policy exercises that complement practical hands-on work was affirmed by an intern placed in a public records disclosure office: “Data ethics…, liability, and moral issues that come with openly publishing research data—I knew this was important but didn’t really realize what it looked like in practice until working with the county clerk.” Partners also regularly verified the high value of the internship experiences, drawing attention to issues of scale that students were uniquely equipped to address and the particular value of online students that were able to seamlessly work both in-person and remotely.

The extraordinary opportunities provided to students by ODL internships accentuated the need for viable alternatives that give more students exposure to the organizational contexts of public sector work and experience translating classroom education into work for the public good. Our investments in practical demos and lab exercises, as well as classroom interaction with practicing data professionals, have benefited both residential and online students. There is much more to explore, however, with instructional techniques that reduce the gap between in-class instruction and real-world practice and with innovations in micro, team, and distributed internships. As graduates who completed ODL curriculum and field experiences become established in professional positions, we are integrating their assessments and recommendations to further optimize how we educate MLIS students for long-term professional success.

A SURVEY OF PUBLIC LIBRARIES AND OPEN DATA TRENDS

In collaboration with the Washington State Library, ODL conducted a survey to gauge the current state of open data in public libraries across Washington state. The results offer insights on what libraries are planning and doing and the constraints they face in meeting the challenges of the open data movement. For ODL, the trends inform how we can best prepare students for the contemporary library workplace and further support libraries with their open data ambitions. For the state library and other library leaders, the study offers a point of reference for weighing their own priorities and commitments in this new area of library service.

The survey was designed to answer the following questions: What is the current level of interest and activity in open data among public libraries in Washington state? What kinds of initiatives are libraries most interested in pursuing? What do they need to make progress? Additionally, the questions probed for perspectives on how open data initiatives align with the library’s mission, community needs, existing services, as well as support needed to begin or move forward with open data initiatives. The survey instrument was pretested with three practicing public librarians with varying levels of awareness of open data. Invitations to participate in the study were sent directly from the Washington State Librarian to all public library system directors in the state, with five systems distributing the survey to their branch managers, for a total of 114 invitations (60 systems and 54 branches) and a final response rate of 45 percent (see Palmer et al., 2021 for access to the dataset). Below we share highlights from the results, on current open data activities, challenges, expertise, and partnerships, from what we found to be highly encouraging trends overall.

Ambition and Action

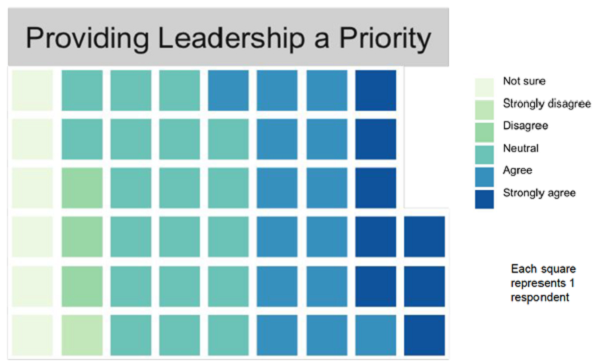

Public libraries of all sizes recognized the importance of open data with a surprising number already active or intending to become active in open data activities. More than 60 percent of respondents indicated that open data initiatives align with the mission of their library. The response was similar for alignment with the interests of their community, with only four small libraries in disagreement. Additionally, 43.1 percent agreed or strongly agreed that “providing leadership for local open data initiatives should be a priority for our library” (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4 Agreement on statement: “Providing leadership for local open data initiatives should be a priority for our library.” |

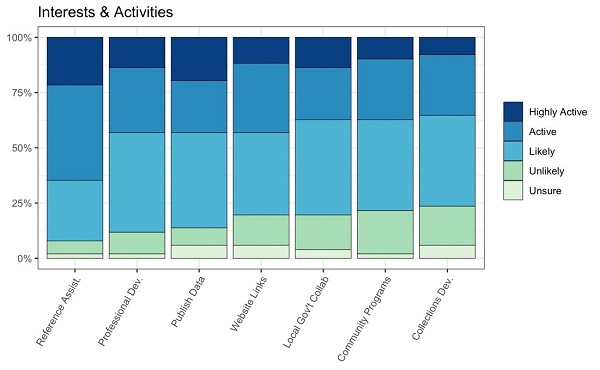

Current open data activities (Figure 5) were most prominent in reference services, with 43.1 percent already active and only 5.9 percent indicating they were unlikely to become active. We were surprised, however, by the limited level of activity in both collections and programs. A few small and medium libraries were highly active in both areas, yet across the pool of respondents 17.7 percent were unlikely to “build collections of open data of value to [their] community,” and 19.6 percent were unlikely to “offer programs for the community on the benefits and use of open data.” The lower interest in these areas is worth exploring further, since, in the library literature, case studies on public library contributions to developing open data portals and public open data programs seem as prominent as reports of reference work with open data (e.g., Carruthers, 2014; Hazlett, 2016).

The second strongest area of activity was in data publishing—that is, libraries making their own data openly available to the public. More than 33 percent of libraries are active. Of the 19.6 percent indicating they are “highly active,” almost half were small libraries with service populations under 25,000. While there is still much to learn about what type of data libraries are releasing, and how, the level of activity in smaller libraries is heartening and aligns with the broader ODL study of data publishing practices, which found no relationship between library open data publishing activity and higher library revenue (Weber & Norlander, 2019). The survey also indicated that a good number of small libraries are already collaborating with local government agencies to make data available to the public. As we’ve seen working with ODL partners, libraries of moderate size and resources can be highly successful in catalyzing change and innovation.

|

Figure 5 Response levels for matrix question on open data activities: Considering the interests of your local community, indicate your library’s likely or current level of activity. |

Familiar Challenges

At present, technical capacity for open data appears limited in Washington public libraries. Only two libraries “strongly” agreed that “open data initiatives align with our library’s current technical proficiency,” and 21.6 percent agreed. There was no consensus on what positions would be most likely to work on open data, with a fairly balanced split between technical and public services. About half of the respondents expected IT personnel to take up open data activities, with the rest distributed across reference, adult services, and other public facing roles.

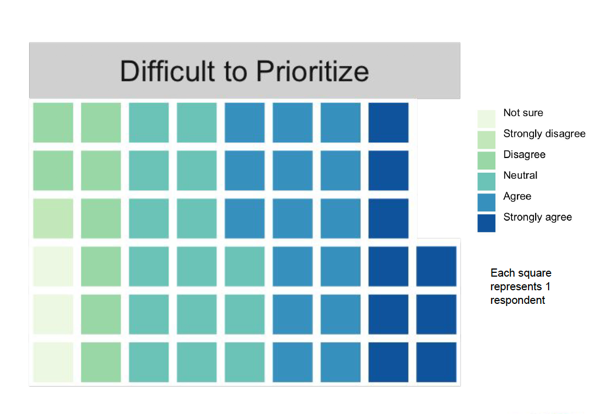

Not surprisingly, resource challenges loomed large. There was strong agreement (47.1 percent) that it is “difficult to prioritize open data initiatives” (Figure 6), with funding identified as a major challenge. For 68.6 percent, “increased operating budget” was essential or of high importance for making progress on their interests or activities in open data; need for grant funding was rated highly by 58.8 percent. Professional development was also a significant factor. More than 56.8 percent indicated educational need in open data work with the public (access, use, and instruction), with fewer, 39.2 percent, interested in education in the more behind the scenes work of data publishing, curation, and infrastructure. Online webinars and in-person workshops were by far the most favored modes for professional development, with preference for online curriculum considerably lower.

|

Figure 6 Agreement on statement: “It will be very difficult for our library to prioritize open data initiatives.” |

Evolving Expertise

The relatively strong uptake of open data in reference services seems a natural evolution of the professional practices involved in reference work, but the need for additional data expertise is imminent. As the volume and complexity of accessible data grows so will the challenges of ensuring integrity in the provision, interpretation, and application of data sources in our work with the public. This is an exciting prospect for reference librarians, as expressed by one of our respondents from a small library: “With the appropriate training, our librarians could be showing our community a richer way to view the world than through a simple Google search.” This idea of appropriate training for current practitioners, rather than new personnel, was reinforced in results showing moderate need for new professional positions for both reference and technical roles. ODL has responded to training demand through webinars and consultation. Currently, we are concentrating on redesigning components of our MLIS curriculum for library continuing education, while also developing data education materials for our partners in state government for their new investments in data stewardship roles.

Partnerships for Proactive Advances

The need for collaboration was widely recognized. A quarter of responding libraries already “collaborate with local government agencies to make their data available to the public,” and, notably, eight had service populations under 99,000. In rating resources needed for aspired open data capacity, “new or improved collaboration with city, state, or other partners” (66.6 percent) was ranked above the need for grant funding (58.8 percent) as essential or highly important, and only slightly below “increased operating budget” (68.6 percent).

Partnerships are also strongly implicated in expressed technology limitations, with more than half (51.0 percent) rating “support from an open data publishing platform” as essential or highly important. We have seen this kind of infrastructure support emerge in Washington state, fostered by the ODL intern who provided liaison between WSL and the Washington State Office of the Chief Information Officer. Through the summer internship, they made significant progress on a groundbreaking pilot effort to curate state open data and on plans for future WSL data publishing and data reference service. Now, through the Open Data Literacy Consultant professional role that emerged, WSL provides support for public libraries across the state to release their data through the state open data portal (data.wa.gov). Just as importantly, the partnership has broadened awareness within Washington state agencies of the valuable expertise librarians can contribute to digital collections, metadata, engagement with user communities, and other areas essential to successful data access systems and services.

LOOKING AHEAD

While we have used the infomediary lens to frame this discussion of our work on open data in libraries, our experience with ODL points to the need for a more proactive conception of our professional responsibilities in advancing open data for the public good. Making open data an integral part of the information resources and services provided to the public will depend on active brokering of strong, productive partnerships between public libraries and government agencies. These strategic alliances can manage resource constraints and build on respective strengths to mobilize data, technologies, and expertise required to launch and sustain open data services. They can bring together important public sector perspectives to help set investment priorities, focusing on direct benefits to local communities and broader impacts for civic engagement, digital equity, and institutional and regional strategic planning. We are optimistic that with the right open data education and partnerships, public libraries can promote, and help lead, this crucial dimension of information access and literacy in the digital age.

Carole L. Palmer (Professor and Associate Dean for Research), Nic Weber (Assistant Professor), and Bree Norlander (Data Scientist, Technology & Social Change Group) are at the Information School, University of Washington. Kaitlin Throgmorton is now Bioinformatics Analyst at Sage Bionetworks. Please direct inquiries to Carole Palmer at clpalmer@uw.edu.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of our collaborators. Will Saunders, in the Washington State Office of the Chief Information Officer, was instrumental in curriculum, and internship design and placement. Cindy Aden, former Washington State Librarian; Kathleen Sullivan, WSL Open Data Literacy Consultant; and Evelyn Lindberg, State Data Coordinator, have been invaluable contributors to survey development and distribution and mentoring of interns. We also acknowledge the contributions of our survey pre-testers. This project is supported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Laura Bush 21st Century Librarian Program, grant #RE-40-16-0015-16.

References

Allen L., Stewart, C., & Wright, S. (2017). Strategic open data preservation: Roles and opportunities for broader engagement by librarians and the public. College & Research Libraries News, 78(9). https://crln.acrl.org/index.php/crlnews/article/view/16771/18312

Bertot, J. C., Jaeger, P. T., Langa, L. A., & McClure, C. R. (2006). Public access computing and Internet access in public libraries: The role of public libraries in e-government and emergency situations. First Monday, 11(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v11i9.1392

Carruthers, A. (2014). Open Data Day Hackathon 2014 at Edmonton Public Library. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v9i2.3121

Davies, T. G., & Bawa, Z. A. (2012). The promises and perils of Open Government Data (OGD). The Journal of Community Informatics, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v8i2.3035

Enis, M. (2020). Civic data partnerships. Library Journal, 145(1), 26-28.

Hazlett, D. R. (2016). Libraries develop open data training program: Funding provided by Knight News Challenge award. Library Journal, 141(4), 24–26.

IFLA. (2020, March 6). Libraries and open data. SpeakUP! https://blogs.ifla.org/faife/2020/03/06/libraries-and-open-data/

Ostler, K. R., Norlander, B., & Weber, N. (2020). Using open data to inform public library branch services, Public Library Quarterly, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2020.1798206

Palmer, C. L., Weber, N., Throgmorton, K, & Norlander, B. (2021). Data for Public Libraries and Open Government Data: Partnerships for Progress [Data set]. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4557675

Robinson, P., & Mather, L.W. (2017). Open data community maturity: Libraries as civic infomediaries. Journal of the Urban and Regional Information Systems Association, 28(1), 31-38.

Weber, N., & Norlander, B. (2019). Open data publishing by public libraries. ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL), Champaign, IL, pp. 158-161, https://doi.org/10.1109/JCDL.2019.00031.

Weber, N., Norlander, B., & Palmer, C. L. (2018). Advancing open data: Aligning education with public sector data challenges. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science & Technology Annual Meeting, 55(1), 927-928.

Whitacre, B., & Rhinesmith, C. (2015). Public libraries and residential broadband adoption: Do more computers lead to higher rates? Government Information Quarterly 32(2), 164-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.02.007

Yoon, A., Copeland, A., & McNally, P. J. (2018). Empowering communities with data: Role of data intermediaries for communities’ data utilization. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 55(1), 583-592. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2018.14505501063

Source : libraryjournal.com

Dunia Perpustakaan Informasi Lengkap Seputar Dunia Perpustakaan

Dunia Perpustakaan Informasi Lengkap Seputar Dunia Perpustakaan